Music ∷ Sam Porter

Show Artwork ∷ Nikolaos Pirounakis

Episode Artwork ∷ Lily Meek

“In recent years, we’ve been looking for new artists. We’ve found some of the brightest, most talented young people there are. But the search continues.

“We’re looking for men and women with artistic flair. People who are attracted to the Disney style and tradition of animated storytelling. We’re looking for people talented enough to create new worlds of believable fantasy and a new generation of colourful Disney characters.”

The brochure was filled with full-colour photographs of Disney artists at work and visual material not just from the films of the past but the films of Disney’s future. This included pencil animation from ‘The Rescuers’ and concept art for ‘The Fox and the Hound’, but towards the middle of the brochure, two pages had been devoted to projects still in development. In the centre was an intriguing pastel drawing of a terrifying horned figure on a throne. The film, the brochure promised, would be “a Tolkienesque folktale of an evil sorcerer who raises an army of the dead to carry out his plans of conquest.”

This tantalising and mysterious image was enough to encourage many aspiring young artists to apply for a position at the studio. Within animation circles, this project was already legendary. After a decade of successful yet modest films, this would be their most ambitious animated production since the death of Walt Disney, a fantasy epic akin to the great Disney classics of the past. Throughout development and early production, many saw it as their opportunity to make the ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ of their generation.

Instead, it would become the most infamous failure in animation history.

So much so soon, to rest on his young shoulders.

In the mythical land of Prydain, young assistant pig keeper Taran (Grant Bardsley) lives in a secluded hamlet with wise sorcerer Dalben (Freddie Jones) and his oracular pig Hen Wen. In one of her visions, Hen Wen predicts the return of the evil Horned King (John Hurt) and tells of his search for a mysterious black cauldron able to resurrect the dead. Only Hen Wen can tell him where the cauldron is, so Dalben sends Taran away with her to hide. After being distracted by a strange and perpetually hungry creature named Gurgi (John Byner), Hen Wen is kidnapped by the Horned King’s winged dragons, the gwythaints. Taran attempts to save her from the Horned King’s castle, but while he is able to help her escape, Taran is captured and locked in the dungeons. Here he meets the spirited Princess Eilonwy (Susan Sheridan) and hapless minstrel Fflewddur Flflam (Nigel Hawthorne), and together they escape, during which time Taran acquires a magic sword. After a reunion with Gurgi and a short detour into the underground kingdom of the Fair Folk, they travel to the marshes of Morva in search of the cauldron. Three witches possess it and exchange it for Taran’s sword, informing them that the only way to destroy it is for someone to willingly sacrifice themselves into it. Very soon, they are once again captured and the Horned King uses the cauldron to raise an army of the dead, but is defeated when Gurgi willingly throws himself into the cauldron. The witches try to take the cauldron back, but Taran strikes a bargain with them for Gurgi’s life, and the team of friends are reunited once more.

‘The Black Cauldron’, the 25th Disney animated feature film, is based on the acclaimed series of fantasy novels for young readers, ‘The Chronicles of Prydain’ by Lloyd Alexander. An author of almost 40 books, Alexander is best known for his works for children, particularly the five-volume ‘Prydain’ series inspired by the tales from Welsh mythology known collectively as the ‘Mabinogion’, the earliest prose stories in British literature. “From as far back as I can remember,” recalled Alexander in 1999, “I always loved the King Arthur stories, fairy tales, mythology - things like that. So it was very natural for me when I came to write the Prydain books to sort of follow that direction. I had always been interested in mythology. I suppose my brief stay in Wales during World War II influenced my writing too. It was an amazing country. It has marvelous castles and scenery. It has its own language. It was quite a big experience for me. I'm sure that stayed in my mind for a good many years and became part of the raw material for the Prydain books.”

The first book, ‘The Book of Three’, was published in 1964 to warm reviews, and over the next seven years, Alexander would write four further volumes - ‘The Black Cauldron’ (1965), ‘The Castle of Llyr’ (1966), ‘Taran Wanderer’ (1967) and ‘The High King’ (1968), with the fifth volume receiving the John Newbery Medal from the Association for Library Service to Children. Alexander also published a series of accompanying short stories set in the world of Prydain to complement the books.

The journey to bring ‘The Black Cauldron’ to the screen as a Disney animated feature would take fourteen years, its production forced to navigate through a tumultuous period of artistic conflict, corporate unrest and a collision of philosophies over the fundamental nature of Disney animation. Since its disastrous release in 1985, the film has attained an almost mythical status as Disney’s most notorious flop. For over a decade after its release, it wasn’t even possible to see it.

This is the story of ‘The Black Cauldron’, a film on which a whole generation of Disney artists pinned hopes of greatness, hopes that would ultimately be dashed in humiliating fashion. Its creation, begun with overwhelming enthusiasm, would turn into an endless battle over what it was and what it could represent. Many of the Disney animated films were born out of conflict, disagreement and unfortunate circumstances. Some even bear their scars. None emerged from their tortured birth as battered or as broken as this one.

I was reaching out to make a more ‘adult’ version of our typical animation. I thought it had chances.

Their marker was ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’. Even though he had overseen many great films in the decades following its release, ‘Snow White’ was still seen as Walt and the studio’s greatest achievement, and if this next phase for Disney animation was going to make its mark, it needed its own ‘Snow White’. Everyone believed that this adaptation of ‘The Chronicles of Prydain’ could be just that. Looking back on the project in 1996, Johnston remarked with regret that “it could have been as good as ‘Snow White’.”

Pre-production began in 1973, the same year as the release of ‘Robin Hood’. The first challenge was how to approach a story of this magnitude. Contrary to popular belief, Disney never intended the film as the start of a franchise; the plan was always to make a single film out of the five-book ‘Prydain’ series. The problem was that the books featured hundreds of characters, numerous locations and enormous set-pieces. Adapting the entire series as a single film was impossible, so a more creative approach was needed. A number of story artists were involved in the early development, including Ken Anderson, but none were able to crack the story.

One of the artists tasked with tackling the adaptation was veteran Disney artist Mel Shaw. Born on December 19, 1914, Shaw had started his career in Hollywood designing silent movie title cards and working as a storyboard artist before moving into animation at the studio run by animators Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising. In 1937, Walt subcontracted Harman and Ising to work on the Silly Symphony short ‘Merbabies’, while they loaned Disney some of their ink and paint artists to work on ‘Snow White’. When ‘Merbabies’ was complete, Shaw was made an offer by Disney to come and work for them, and he joined the studio in 1938. Though beginning as an animator, Shaw’s major contribution to the early Disney classics was in visual and story development, in particular for ‘Bambi’. In 1943, he left Disney after being drafted into the Army, but left behind significant contributions to future Disney films, including ‘The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad’ and ‘The Sword in the Stone’.

After the war, he established his own animation studio with artist Bob Allen, but in 1970, was asked to return to Disney by Ron Miller. “As we talked”, Shaw later recalled, “it became clear to me that [Miller] was anxious to revitalise the animation department. As he put it, ‘Animation is what made the studio in the first place and it should be rebuilt!’ He asked me if I would be interested in coming back to help out. I reminded Ron that I had my own studio to run but I would be glad to return to the studio on a part-time basis.”

When Shaw returned to Disney, he was presented with two projects to choose from, ‘The Chronicles of Prydain’ or ‘The Fox and the Hound’, but his first task was to help Wolfgang Reitherman with the opening title sequence for ‘The Rescuers’. Working from a demo of the opening song, Shaw created a series of pastel sketches to chart the journey of the message in the bottle. Reitherman was so impressed that he decided to use the static artworks for the titles with only minimal enhancements.

“The next one I did was ‘The Prydain Chronicles’”, recalled Shaw, “I read the books… and I met the author. He was out here at the time, and that impressed me, and he impressed me… And that one I spent a lot more time on. They gave me a great big room up there, so I could bring in the drawings and put them up on storyboards.”

Shaw began work on developing a film from the ‘Prydain’ books, delivering a staggering collection of over 200 pastel artworks. Rather than trying to condense the novels into a single film, he conceptualised moments from across the entire series, hoping that this would guide him in crafting the story. He also knew how to present the artwork in the most dramatic way possible. Shaw was the first artist to make use of the Leica reel process in the 1930s, and used those skills to great effect to give a sense of the film he was developing, often pairing it with a recording of Carl Orff’s ‘Carmina Burana’. The response to Shaw’s work was immediate and ecstatic. It was some of the most exciting conceptual work the studio had seen in years, suggesting a project on a scale they had never attempted before, and the idea that it could be comparable to the early Disney classics started to spread.

For the new generation of Disney artists in particular, this project was exactly what they had been hoping for. They had played second-fiddle on ‘The Aristocats’ and ‘Robin Hood’, but despite their charm, those projects were artistically modest. Don Bluth had become the voice of this group, many of whom had been working animators before being taken under the wing of Disney and subscribed to Bluth’s mission to return Disney animation to its former glory. They were ready to prove themselves on something dense and distinctive, and what Shaw was offering with ‘Prydain’ might give them that chance.

Ron Miller was also enamoured with Shaw’s artwork, and was determined to preserve its dark, mysterious quality. It would be an enormous gamble in terms of tone and texture, but like the younger artists, Miller was determined to prove what Walt Disney Productions was capable of. Though they shared Miller’s enthusiasm, the remaining Nine Old Men were intimidated by the scale of Shaw’s film. They weren’t confident that the new artists were up to the challenge. Miller agreed, and in 1975, they were put to work on ‘The Rescuers’, kept under the watchful eye of Reitherman, Thomas, Johnston and Milt Kahl. This more modest production, along with the short ‘The Small One’, would be a means of sharpening their skills in preparation for the more ambitious film. The ‘Prydain’ project, now named ‘The Black Cauldron’ after the second book in the series, was scheduled for a Christmas 1980 release.

Don Bluth and his colleagues did not take the news well. They disagreed with the senior animators; they felt they were fully up to the challenge. Many of them had developed ‘The Rescuers’ in the early 70s, but in the hands of the senior animation staff, they felt the project was becoming too sanitised, too safe. It was in the wake of this decision that Bluth began work on his own personal project, ‘Banjo the Woodpile Cat’, made after hours in his garage.

In the mid-1970s, development on ‘The Black Cauldron’ moved slowly, but the enthusiasm was still in the air, even from the disgruntled younger animators. Speaking with journalist John Culhane in 1976, Bluth remarked “Right now, enthusiasm for a story called ‘The Black Cauldron’ is boiling through the studio, and we hope that the new generation can touch people with that story in ways that Walt never dreamed of.” In the meantime, story artist Vance Gerry had been tasked with creating storyboards for the film, making decisions on character, plot and location. Gerry decided that the villain of the film should be the Horned King, a character who only appears in the first book, ‘The Book of Three’. In Gerry’s version of the film, the Horned King was a big-bellied, red-haired viking with a bad temper. It was thought that the project might benefit from an experienced screenwriter, so British television dramatist Rosemary Anne Sisson was brought on board.

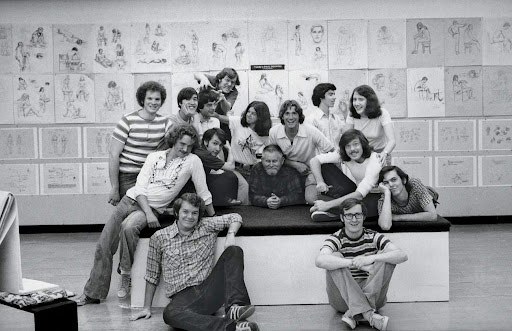

Back, from left - John Lansizero, Darren Van Citters, Brett Thompson, John Lasseter, Leslie Margolin, Mark Cedeno, Paul Nowak and Nancy Beiman

Middle, from left - Jerry Rees, Bruce Morris, Elmer Plummer (teacher), Brad Bird and John Lefler

Front, from left - Harry Sabin and John Musker

Another group who were enthusiastic about ‘The Black Cauldron’ were the artists coming to Disney through the Character Animation Program at CalArts. Launched in September 1975, the first graduating class included future directors John Lasseter, Brad Bird and John Musker, the latter of whom became the de-facto leader of the CalArts graduates at Disney. Unlike the artists trained through the studio’s Talent Development Program, the CalArts animators were younger, less-experienced and bursting with combustible enthusiasm. They were also more familiar with the character-driven principles of animation championed by Reitherman, and their boisterous work ethic put them in conflict with the more serious Bluth and his colleagues.

The one thing all three camps could agree on - the Reitherman camp, the Bluth camp and the CalArts camp - was that ‘The Black Cauldron’ had the potential to be something special, and everyone was restless to get started. It came as a huge blow when, in August 1978, Ron Miller decided to push the release date once again. He was still convinced the animators weren’t ready, and settled on a release date of Christmas 1984 instead. The far less ambitious ‘The Fox and the Hound’ would take the original Christmas 1980 slot.

This decision was yet another contributing factor to the rebellion led by Don Bluth in September 1979. It suggested a lack of confidence in the artists from the executive staff, and many saw ‘The Fox and the Hound’ as another regression for Disney animation. In his chat with Culhane in 1976, Bluth had remarked, “See, we haven't been telling better stories than ‘Snow White’, and we should be. We're doing the same thing over and over again, but we're not doing it any better.” Rather than sitting and waiting for Disney to give them their chance, Bluth and his colleagues left to make their own ambitious animated fantasy epic, ‘The Secret of NIMH’. As a result, the antagonistic energy within the animation department dissipated, and work continued on ‘The Fox and the Hound’ and preparing ‘The Black Cauldron’.

In the meantime, Mel Shaw had been hard at work developing another project, an adaptation of Mary Stewart’s 1971 fantasy novel ‘The Little Broomstick’. Reitherman was also very enthusiastic about this project, but Miller was concerned about its scale. As ‘The Fox and the Hound’ was nearing completion, a decision had to be made on what film would follow, the in-development ‘The Black Cauldron’ or the new project ‘The Little Broomstick’. The comparable scale of the two films meant that only one could proceed. In the end, and much to Reitherman’s disappointment, ‘The Black Cauldron’ won and ‘The Little Broomstick’ was shelved.

Artist and CalArts graduate Mike Peraza had worked with Shaw on ‘The Little Broomstick’. “The older generation, Frank and Ollie and all the other Disney veterans”, he later recalled, “liked ‘The Little Broomstick’. But the younger generation, almost to a person, were all excited about ‘The Black Cauldron’. You have to remember though, we had been listening for a couple of years how ‘The Black Cauldron’ was our chance to do our own ‘Snow White’, something we could call our own… [Mel had] put a lot of work into it, even though ‘The Black Cauldron’ film ultimately didn’t reflect Mel’s story. His version of ‘Cauldron’ was amazing.”

Financing for ‘The Black Cauldron’ was finalised in 1979, and in May 1981, a few months before the release of ‘The Fox and the Hound’, the film finally entered production. It had been a decade since the studio had bought the rights to Alexander’s series, but the film now had an incredible visual guide in Mel Shaw’s concept art, the literary backing of Rosemary Anne Sisson, a strong directing team that included the young but talented John Musker, the enthusiasm and dedication of the entire animation department and the confidence of Ron Miller and the studio. Their chance had finally come to deliver the great animated classic of their generation.

Very soon, that enthusiasm would give way to blind panic.

As ‘The Black Cauldron’ entered production, Walt Disney Productions was preparing to launch a number of ambitious new enterprises. An altered version of Walt’s dream futuristic city EPCOT was finally being built adjacent to Walt Disney World, and in the film department, they were attempting something unheard of, a feature film making extensive use of computer-generated imagery, not as window dressing but as an integral part of the narrative.

Working from Vance Gerry’s storyboards and Rosemary Anne Sisson’s screenplay, it was decided to focus ‘The Black Cauldron’ on the first two volumes of ‘The Chronicles of Prydain’, ‘The Book of Three’ and ‘The Black Cauldron’. John Musker, the brilliant CalArts graduate whom many of the young animators had rallied around, was brought on as director. This was a huge vote of confidence in his abilities, since Musker had no directing credits of any kind. Only three years after joining Disney, he was being handed the reins of a highly anticipated, high profile production. The role of producer went to Art Stevens, who was finishing up his directing duties on ‘The Fox and the Hound’.

Work began in earnest developing the characters and environments in the film, with the Disney artists encouraged to think outside of the box. One of the artists assigned to character development on the film was Tim Burton. While his work on ‘The Fox and the Hound’ had not meshed well with his artistic sensibilities, ‘The Black Cauldron’ was a perfect fit for Burton’s quirky, gothic style. Mike Gabriel, who joined Disney as an in-betweener in 1979 and worked as an animator on the film, later said of Burton's work, “That’s what we were excited about... His concepts were just incredible to us. We were going nuts with his stuff. He had the coolest ideas for the villain, the Horned King. The Horned King had puppets on his hands, and he talked to his puppets, and then the Gwythaints were actually made out of these long skeletal, kind of like ‘Edward Scissorhand’ figures. The hand itself was the bird, and it was just these hands flapping around. Brilliant stuff that would have redefined what is a Disney animated film.”

To lend the film prestige, it was also decided to shoot the film in Super Technirama 70, the same format that ‘Sleeping Beauty’ had been shot in and the first animated film to use the format since. In recent years, Disney had favoured a 1.78:1 aspect ratio, often matted from 1.66:1, but ‘The Black Cauldron’ would have a significantly wider aspect ratio of 2.20:1, adding over 40% more image to the frame. This had caused significant problems on ‘Sleeping Beauty’, but the department was now more prepared, handing out detailed guides to the animators on how best to work with the wider frame.

Once production was complete on ‘The Fox and the Hound’, it was decided to transfer the directing team of Richard Rich and Ted Berman to ‘The Black Cauldron’ to assist Musker. Rich and Berman had co-directed ‘The Fox and the Hound’ with ‘Cauldron’ producer Art Stevens, and this imbalance between the veteran Disney artists and the younger Musker began to cause tension over the direction the film was taking. Miller was forced to step in and decided to replace Stevens as producer with one better suited to solve any conflicts that might arise. He approached layout artist Joe Hale. “Ron Miller called me up and asked me if I would take over as producer on ‘The Black Cauldron’”, he later recalled, “... but I didn’t want to do it because a good friend of mine, Art Stevens, was the producer and I just didn’t feel right about it. And at that time, I was more interested in live action and I talked to Ron about second unit live action directing. Anyway, Ron finally told me that whether I took the job or not, Art was gonna be replaced by someone else. So, I took over ‘The Black Cauldron’.”

Very quickly, Hale began to make significant decisions on the direction of ‘Cauldron’. He rejected all of Burton’s artwork and reassigned him to other projects. He also began revising the story, bringing in new story artists and working to further condense the two books into a workable film. There had now been nearly a decade of story development done for ‘Cauldron’, and Hale saw it as his task to “pull the whole thing together.”

Unhappy with Vance Gerry’s original concept of the Horned King as a hot-blooded viking, Hale reconceived the character as a skeletal, threatening figure, pulling on elements from the various villains in the book series. He also turned to the now-retired Milt Kahl, asking him if he would help out with character designs for Taran, Eilonwy, Fflewddur, Gurgi and the Horned King. Kahl had been responsible for some of the most memorable Disney characters, but Hale had made a gross miscalculation as to Kahl’s process. Rather than creating character designs from his own imagination, Kahl relied on concept art to respond to, none of which Hale had thought to send him. All of his designs recall earlier Disney characters, but while most were eventually rejected, his designs for Taran and Eilonwy remain mostly intact in the film, the former a little too reminiscent of Peter Pan and the latter of Alice or Aurora.

These boisterous creative decisions soon began to create further tension within the production team. Rosemary Anne Sisson stepped down as screenwriter, citing creative differences with the directing team. Rather than removing Art Stevens from the project entirely, Miller made him the fourth director in the team, and this had thrown the balance against John Musker even further. The young director wasn’t even given any sequences to direct. He and colleague Ron Clements had been working on an adaptation of Eve Titus’ children’s book ‘Basil of Baker Street’, so along with Clements, who had been working on story development on ‘Cauldron’, Musker requested to be taken off the film and assigned to ‘Basil’ instead. ““We were the odd men out”, Musker later recalled, “along with a few other people who wanted the story and the characters to go in a certain way, and the people in charge didn’t see it that way. It was very frustrating.” An expansion of the department’s project development program allowed for two films to be in production simultaneously, so in 1982, both men were reassigned to the other film, Musker as co-director and Clements as story artist.

Very soon other artists began to follow Musker and Clements. Glen Keane, who had made such a significant mark on ‘The Fox and the Hound’, was among them. “Everything I did was being thrown out”, he recalled. “They just did not like anything I was doing. Eventually the directors asked me if I would just leave the film and go do something different.” Storyboard artist Michael Giaimo also saw his work on the film rejected for being “too broad”. ‘The Black Cauldron’, once the hopes and dreams of the new generation of Disney artists, was now back in control of Disney veterans.

In July 1982, Aurora Productions released Don Bluth’s first animated feature, ‘The Secret of NIMH’. While it was only modestly successful at the box office, the film garnered wide-spread critical acclaim, many praising it as an artistic triumph. To make matters worse, the dark Gothic tone of the film was uncomfortably similar to what Miller had been hoping for ‘The Black Cauldron’, Bluth imbuing a fantastical subplot not present in the original Robert C. O’Brien novel.

A few weeks later, ‘Cauldron’ was delivered another blow when animators across the US went on strike. There had been growing concerns over the outsourcing of animation to artists overseas, especially for television. The strike would continue for ten weeks until September 1982, during which time ‘The Black Cauldron’ was held together by a makeshift crew of artists not part of the strike. To make matters worse, they realised that the guides they had been using for the Super Technirama 70 frame were incorrect when compared to those used on ‘Sleeping Beauty’, and many of the sequences needed to be reworked.

On the 9th of December 1982, the first cels for ‘The Black Cauldron’ arrived at the inking and painting department. There were still conflicts over the story, but with the Christmas 1984 release date looming on the horizon, work needed to pick up steam. The film was shaping up to be a monster of a production, and yet after so long in development, there was still no agreement over what the film actually was. Whatever chaos it had weathered was nothing compared with what was to come.

- Wikipedia on The Black Cauldron, Lloyd Alexander, The Chronicles of Prydain, Mel Shaw, Harmen and Ising, The Great Mouse Detective, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Michael Eisner, Roy E. Disney, The Walt Disney Company, Saul Steinberg and The Care Bears Movie.

- The Disney Studio Story, Richard Hollis and Brian Sibley, 1988

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume V - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Early Renaissance (The 1970s and 1980s), Didier Ghez, 2019

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume VI - The Hidden Art of Disney’s New Golden Age (The 1990s to 2010s), Didier Ghez, 2020

- Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation, Mindy Johnson, 2017

- Disneywar, James B. Stewart, 2005

- The Troubled History of Disney's "The Black Cauldron" & The Lost Cut Scenes, Yesterworld Entertainment, May 17, 2021

- Lloyd Alexander Interview Transcript, Scholastic, January 26, 1999

- Ollie Johnston Interview: Part 1, Norskanimasjon, 1996

- John and Rom Mention ‘The Unmentionable’, interview with Michael Mallory, Animation Magazine, September 7, 2012

- Milk Kahl’s Black Cauldron, Deja View, February 9, 2013

- Disney is Looking…, Deja View, February 27, 2012

- Cauldron of Chaos, Ink and Paint Club: Memories of the House of Mouse by Mike Peraza, March - April 2010

- ‘Black Cauldron, a Brew of Vintage Disney Animation’, Michael Blowen, New York Times, August 3, 1985

- The Black Cauldron: Producer Joe Hale talks munchings and crunchings…, Jérémie Noyer, Animated Views, September 17, 2010

- 'The Black Cauldron': What Went Wrong, Jim Hill Media, February 9, 2006

- Revisiting The Black Cauldron, Dan Kois, Slate, October 19, 2010