Music ∷ Sam Porter

Show Artwork ∷ Nikolaos Pirounakis

Episode Artwork ∷ Lily Meek

In 1952, Sammy Fain and Jack Lawrence were contracted to write the songs for the film, after the successful work Fain had done for ‘Alice in Wonderland’ and ‘Peter Pan’. They wrote a full suite of songs to accompany the story treatment being prepared, but a year later, Walt began to worry that a traditional Disney song score wouldn’t match with the visual language Eyvind Earle was developing. Not only did ‘Sleeping Beauty’ need to look different, it needed to sound different.

Walt decided that the film would use Tchaikovsky’s ballet as its score, adapted to fit their needs. All of Fain and Lawrence’s songs were rejected, with the exception of ‘Once Upon A Dream’, which had used the Waltz from Act I of the ballet as the basis for its melody. At first, Walter Schumman was given the task of adapting the ballet, but he soon quit over creative differences with Walt. Instead, the job of turning the beloved ballet into a full symphonic score was given to composer George Bruns.

Bruns had joined the studio as an arranger in 1953. He had never attempted anything of the scale of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ before, but had been recommended for the job by Ward Kimbell. “It would have been much easier to write an original score,” he said in 1958. “But [the ballet] is rich in melody, as much as Tchaikovsky is. It was a matter of choosing which melodies to use.”

His adaptation of the ballet took three years to complete, balancing it with his work for the ‘Davy Crockett’ series on the ‘Disneyland’ TV show. Almost every moment of the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ score was extracted from the ballet, with Bruns filling in the musical gaps where necessary. In addition to ‘Once Upon A Dream’, a number of other songs were added to the score, once again using music from the ballet arranged by Bruns, with lyrics by Tom Adair, Ed Penner, Winston Hibler and Ted Sears. When it came to the scene where King Stefan and King Hubert drank together, Bruns couldn’t find an appropriate melody for the ballet, so ‘Skumps (Drinking Song)’ is the only song in the film not rooted in Tchaikovsky. The most important principle in Bruns’ score though was that any new material must always sound like Tchaikovsky, so that the score would be as holistic as the visuals.

When it came time to record Bruns’ completed score, Walt made another major technical decision - to match the scope of the Super Technorama 70mm image, the film would be recorded in four-track stereo sound, and released in six-track stereo. He had made a similar bold decision with ‘Fantasia’ in 1940, but despite the fact that the cost of Fantasound had been one of the reasons for that film’s box office failure, he was sure this would add value to ‘Sleeping Beauty’ for the public. The vocal performances were recorded in Los Angeles, but when a musician’s strike began, they were forced to look elsewhere to record the score, settling on a new state-of-the-art recording facility in Berlin. George Bruns’ score for ‘Sleeping Beauty’ was recorded with the Graunke Symphony Orchestra, with Bruns conducting, between the 8th of September and the 25th of November 1958. When the digital restoration of the film was undertaken for its 50th anniversary in 2009, the complete original recording sessions were found in startling, pristine condition.

In the booth overseeing the recording was Disneyland Records musical director Tutti Camarata. After hearing the clarity of the stereo recording, Camarata approached Walt with the idea of releasing Bruns’ score as a commercial album. The studio had released the first commercial soundtrack with ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ in 1937, but that had only featured the songs. The soundtrack for ‘Sleeping Beauty’ would be the first-ever commercial release of an orchestral film score, and the first true stereo soundtrack from an animated film.

While much praise is heaped upon Eyvind Earle’s extraordinary visual designs, George Bruns’ score from ‘Sleeping Beauty’ is equally as triumphant, one that was recognised with both an Oscar and a Grammy nomination. It still stands as one of the best scores in the Disney canon, and one of the greatest communions between visual and music in any film.

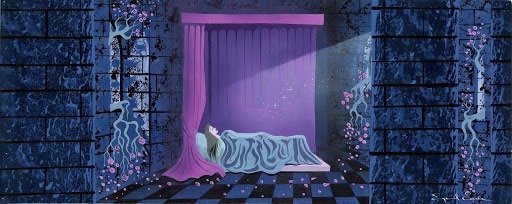

THE DRAGON BATTLE Of all the remarkable sequences in ‘Sleeping Beauty’, none are as astounding as the final battle between Prince Phillip and Maleficent. A perfect storm of everything that is great about the film, it demonstrates the apotheosis of its pursuit for perfection.

I remember reading something at a film festival here in Los Angeles, in which they listed the battle with Maleficent as the dragon as probably the greatest achievement graphically on 70mm film that had ever been done to that point and probably would ever be done in the future.

The sequence was a collaboration between supervising director Clyde Geronimi and directing animator Wolfgang Reitherman, who joined Geronimi on the sequence after he had taken over the film from Eric Larson. Later asked about the sequence, Reitherman (who would go on to direct many of the Disney animated features in the 1970s), said, "We took the approach that we were going to kill that damned prince!"

The sequence would be Reitherman’s greatest achievement, taking the visceral drama of Eyvind Earle’s concept art and matching it to the raw fury of George Bruns’ score. To ensure that the music and animation were in harmony, a full orchestral recording of the track was completed before work on the animation began, so that Reitherman, Geronimi and their team could work off the rhythm and timing of Bruns’ score.

In Vulture’s 2020 article listing the 100 most influential sequences in animation, which included the Dragon battle in ‘Sleeping Beauty’, they wrote, “Phillip’s galloping horse and Maleficent’s transformation are clear images of good and evil that are immediately understood and brought to a thrilling conclusion of explosive greens, twisting brambles, and the deadly fires of Hell.” The sequence is regarded as one of the greatest in any animated film. It has been sighted numerous times as a landmark, not just in animation, but in 70mm filmmaking, and in 2008, Oscar-winning filmmaker Guillermo Del Toro listed Maleficent in dragon form as one of the greatest screen dragons, “a triumph of elegance of colour and design”.

Despite some rare exceptions, the long-standing sexism towards women in animation still existed at Disney, with women usually only given opportunities outside of the Ink & Paint department under exceptional circumstances. The demands of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ meant that the supervising animators couldn’t be so pedantic, and for the first time, a program was set up for women to train as assistant animators.

There were relatively few women in the animation process industry-wise, except in Ink & Paint. On ‘Sleeping Beauty’, they needed some fresh talent, so my timing couldn’t have been better… There was so much creative energy in that studio, and that training led us on to other things later.

The program was initially overseen by animator Johnny Bond. The female artists were put through training, with the option of additional night classes. From those participants, the most promising were hired as in-betweeners.

As it turned out, the patience, skill, determination, empathy and attention to detail of these female artists became an enormous asset on ‘Sleeping Beauty’. “It was an animated motion picture perfectly suited to the unique sensibilities inherent in most women artists,” said animator Floyd Norman in 2015, who worked as an in-betweener on ‘Sleeping Beauty’ and was the first African-American artist employed at the studio full-time. “Male artists, frustrated with drawings where the weight of an eyelash was considered important, often deferred to the skill and patience of their female colleagues.”

The film would also prove to be a masterpiece for the women in Ink & Paint. The extreme level of detail in the design and animation required even more meticulous work than they had attempted before, and though it took longer, the results were breathtaking. For the Inkers in particular, the film showed them at the height of their craft, with the width of every line scrutinised and perfected. “Oh, they were amazing, those Inkers,” said assistant animator Jane Baer in 2015. “The meticulous detail in the eyes of the character and every curl on the princess, it was something else.”

The necessities on ‘Sleeping Beauty’ offered an long-needed opportunity for the women of Walt Disney Production, and not only was it an opportunity they embraced, but one in which they excelled. There was a new energy to the work, a new perspective and texture that hadn’t been there before.

That energy would not last. The worst was yet to come.

- STORY: During story development, Walt instructed storyman Bill Peet to redo a sequence he’d been working on. When he refused, Walt removed him from the project and made him work on a Peter Pan Peanut Butter commercial instead.

- CAST: Mary Costa was cast as Aurora after she had been seen performing at a dinner party at the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music by then-composer Walter Schumman in 1952. A trained opera singer, she had the full, clear voice that Walt wanted for Aurora, but also had a Southern accent. She worked to make her accent more mid-atlantic for the dialogue scenes.

- CAST: Eleanor Audley, who provided the voice of Maleficent, initially turned down the role because she was fighting tuberculosis, and was concerned that her coughing would disrupt the recording sessions. When she had recovered, he finally accepted the role, and also provided the live action reference for the character. Additional reference for the character was provided by assistant animator Jane Fowler.

- CAST: Helene Stanley, who had been the live action reference for Cinderella, returned to do the same for Aurora.

- CAST: Rather than using the voice actors for the live-action reference for the Three Good Fairies, they cast Frances Bavier, Madge Blake and Spring Byington, who were a closer resemblance to the character designs.

- COSTUME: Alice Estes had been a teaching assistant to Marc Davis when she studied at Chouinard. For ‘Sleeping Beauty’, he asked her to design Aurora’s costumes for the live-action reference footage. This was her first costume design assignment with Disney, where she continued to work for many years, including designing the costumes for the auto-animatronics for WED Enterprises. Alice and Marc eventually married.

- ANIMATION: To save time, rotoscoping was used on some of the human characters to capture their realistic motion.

- ANIMATION: Milt Kahl was the supervising animator for Prince Phillip, but found the character boring to work on. He added the character of Sampson the horse to make the work more interesting.

- ANIMATION: Fauna was inspired by a woman Frank Thomas had met in a ladies club in Colorado.

- ANIMATION: The drunk Minstrel was the work of animator John Sibley.

- SUPER TECHNORAMA 70: The negative for the format was so large that it needed to be played through the projector sideways.

‘Sleeping Beauty’ premiered in Los Angeles on January 29 1959. For its initial run, Buena Vista released the film in both 35mm with a monaural track, and 70mm with six-track stereo sound, the latter in a series of showcase screenings.

Critics, in general, were not taken with the film, many of them regarding it as an inadequate copy of ‘Snow White’. "Even the drawing in ‘Sleeping Beauty’ is crude,” wrote Time, “a compromise between sentimental, crayon-book childishness and the sort of cute, commercial cubism that tries to seem daring but is really just square.” The critic in Harrison’s Reports wrote "It is doubtful, however, if adults will find as much satisfaction in ‘Sleeping Beauty’ as they did in ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’, with which this latest effort will be assuredly compared because both stories are in many respects similar. While ‘Beauty’ is unquestionably superior from the viewpoint of the art of animation, it lacks comedy characters that can be compared favorably with the unforgettable Seven Dwarfs."

In its initial theatrical run, the film only made $5.3 million, which meant that, due to its enormous budget, ‘Sleeping Beauty’ was not only a box office failure, but a significant one. It is often remarked that ‘Sleeping Beauty’ was actually the second-biggest box office hit of 1959 behind ‘Ben-Hur’, and that its failure was due entirely to its inability to cover its budget, but this figure also includes earnings from its re-releases over the last fifty years. ‘Sleeping Beauty’ not only wasn’t the second biggest box office hit of 1959, it didn’t even crack the top ten. In fact, it was another Disney production, ‘The Shaggy Dog’, that held the number two spot that year.

‘Sleeping Beauty’ was never re-released in Walt Disney’s lifetime. With its return to theatres in 1970, and through the many re-releases following, it not only recouped its budget but became one of the most successful Disney animated films. For many decades though, it was only seen in Technirama 2.20:1 or a Cinemascope reduction print in 2.35:1, with restorations of the film often using interpositive negatives. For the 50th anniversary restoration in 2009, the original Technicolor negative was used, and ‘Sleeping Beauty’ was finally released in its full 2.55:1 aspect ratio for the first time since 1959.

Today, ‘Sleeping Beauty’ is regarded as the pinnacle of Disney animation. Seen within the context of the Disney canon, it is a monumental achievement, an all-encompassing cinematic experience whose stripped-back narrative, combined with its medieval style and enormous orchestral score, speak to the primal, brutal heart of fairy tales as foundational texts of the human experience. Walt Disney had intended for it to be his magnum opus, and after many, many decades, that is precisely what many believe it to be.

“I think it’s the end of an era, I think it’s the end of a kind of animation that we’ll never see again, a kind of opulence and lavishness and meticulous craftsmanship that is gone now.” - John Canemaker, Disney historian

The film had also intended to be Disney’s great assault on United Productions of America, but by the time the film was finally released, UPA had fallen apart. A series of distribution and rights issues had gutted the small studio, and they were nothing more than a shadow of the one that had posed such a threat to Disney seven years before. ‘Sleeping Beauty’ was supposed to be Walt’s ultimate weapon in a battle for dominance, but by the time it was finished, there wasn’t anyone to battle with.

That year, thanks not just to the failure of ‘Sleeping Beauty’, but a number of film projects, the company reported its first annual loss in a decade. Buena Vista alone had lost $900,000. Walt blamed “a considerable leaning in the part of the public towards pictures involving violence, sex and other such subjects.” As a result, the studio announced a staggering series of lay-offs, reducing the animation staff from over 600 to under 100.

A large portion of the artists who lost their jobs in the fallout from ‘Sleeping Beauty’ were the women who had trained to help complete the film. “I would venture to guess,” said Floyd Norman in 2015, “[that] women would have played a larger role in Disney animation had it not been for the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ layoffs in late 1959.”

Perhaps the greatest repercussion of the failure of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ though was the impact it had on animation itself. It was clear that, if feature animation was to survive at Disney, they needed to find a new cost-effective way to make them, not just in terms of resources but the size of the staff employed to make them. During the making of ‘Bambi’, Ub Iwerks had begun experimenting with a process called xerography, a dry photocopying technique that could eliminate the inking stage and photocopy the clean-up animation directly onto a cel. It hadn’t worked well enough to use in ‘Bambi’, but the studio had tried the process again during the making of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ to move production along. This time, it had proved successful, and in the aftermath of its release, the xerox process presented them with an answer to their problem.

It was decided that, for the next Disney animated feature, the xerox process would be used. In the process, the entire Inking department was closed down. The women that, in ‘Sleeping Beauty’, had properly elevated their techniques to an art form, were now no longer called upon to practice their art anymore, and as a result, ‘Sleeping Beauty’ would be the last work of classic animation ever released by Walt Disney Productions. It had been intended to bring the art of animation to new heights, and instead had blown it apart.

The Silver Age of Disney animation now turned in a new direction. The films to come would look nothing like those that had come before, the familiar texture that had become synonymous with Disney. That lush romanticism would give way to a new, highly graphic, modernist style, one where the principles of Disney and UPA animation would finally collide, and where the art of the animators would be on display like never before. And they would begin with an absolute knock-out, a jazzy and vibrant story of a bloodthirsty socialite, two dalmatians, and many, many, many puppies.

The 1986 US VHS release, the 1997 US Masterpiece Collection VHS release, the 2003 US 2-disc DVD Special Edition, the 2008 US 2-disc Platinum Edition Blu-ray, the 2014 US Diamond Edition and the 2019 US Signature Edition Blu-ray.

The 1986 US VHS release, the 1997 US Masterpiece Collection VHS release, the 2003 US 2-disc DVD Special Edition, the 2008 US 2-disc Platinum Edition Blu-ray, the 2014 US Diamond Edition and the 2019 US Signature Edition Blu-ray.

- In October 1986, ‘Sleeping Beauty’ was first released on VHS, Betamax and Laserdisc. During its release, it sold one million VHS copies, and was the first digitally processed in Hi-Fi stereo. It went into moratorium in March 1988.

- In 1997, the film underwent its first digital restoration, and was re-released on VHS and Laserdisc as part of the Masterpiece Collection. ‘Sleeping Beauty’ made its DVD debut in October 2003 in a 2-disc special edition, which included both the widescreen version (2.35:1) and pan-and-scan version. It also included bonus material from the 1997 release, as well as archival programs, trailers and artwork.

- In October 2008, ‘Sleeping Beauty’ entered the Platinum Edition series, in a 2-disc DVD edition and a 2-disc Blu-ray edition, the first high definition release in the series. For the first time, the film was released on home video in its full 2.55:1 aspect ratio, with a new 7.1 DTS MA track. The set also included a number of new special features, including a PiP audio commentary, new making-of material and the ‘Grand Canyon’ nature short that played before the film during its theatrical run.

- The film has received two subsequent Blu-ray releases, the Diamond Edition in October 2014, which coincided with its Digital HD debut, and as part of the Walt Disney Signature Collection in September 2019. Both editions dropped many of the features from the Platinum Edition.

- The film is available on Disney+.

- Wikipedia on Sleeping Beauty, the original fairy tale, Eyvind Earle, Eric Larson, George Bruns, Floyd Norman, Super Technorama 70, and the Unicorn Tapestries.

- Sleeping Beauty: Platinum Edition, Blu-ray, 2009

- Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, Neal Gabler, 2006

- Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation, Mindy Johnson, 2017

- The Disney Studio Story, Richard Hollis and Brian Sibley, 1988

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume II - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Musical Years (The 1940’s - Part I), Didier Ghez, 2015

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume IV - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Mid-Century Period (The 1950’s and 1960’s), Didier Ghez, 2016

- Sleeping Beauty: The Legacy Collection, soundtrack release notes, Paula Sigman-Lowery, Russell Schroeder and Randy Thornton, Walt Disney Records, 2014

- Interview with Gerry Geronimo, Michael Barrier and Milton Grey, 2015

- The 100 Most Influential Sequences in Animation History, Edited by Eric Vilas-Boas and John Maher, Vulture, October 5 2020

- Walt Disney’s “Sleeping Beauty” Sound Track on Records, Greg Ehrbar Cartoon Research, April 2, 2018