The function of a biopic is often to reveal some unknown truths about their subject, whether that be their origins or how they came to be a figure of note. There's a sense that we should know more about them by the time the credits roll than we do when the lights go down. Some historical figures though prevent such a straightforward approach. Despite their public life, their inner lives are a mystery, shrouded in legend and gossip. The lazy approach would be to fill in those gaps with assumptions and turn the unknowable into some sort of pseudo-fictitious knowable. The more interesting approach though is to maintain that mystery, to embrace the subject's choice to remain hidden and make this the central drama of your portrait - to let the unknowable remain so.

One such figure is the legendary opera singer Maria Callas. Despite being an international superstar, an obsession for tabloids and paparazzi and perhaps the greatest voice of the last century, there is much we don't know about her. She was reticent to talk about herself publicly with any degree of certainty, instead arguing that her performances of the great operatic repertoire spoke for her. The truth was in her singing, and no words could better express that truth. How this woman rose from poverty in Greece to the height of fame, how she fell into one of the great love affairs of the post-war period and how all of it came crashing down is tantalisingly unclear. She may have been photographed by some of the greatest photographers in the world and sold millions of records, but we still don't really know who Maria Callas was.

This makes her the perfect subject for the final movement in Chilean director Pablo Larraín's trilogy of films on iconic women of the 20th century, begun with 'Jackie' (2016) and followed by 'Spencer' (2021). Like Jackie Kennedy and Princess Diana, Callas straddles those rare qualities of being both celebrity and icon, a woman of intense gossip and fascination who also fashioned herself into a mythological figure. And like 'Jackie' and 'Spencer', 'Maria' is chiefly concerned with the question of why someone of such power and privilege might craft themselves into such a figure, enigmatic and mysterious. For Jackie Kennedy, it became an act of self-determination, to take control of her narrative and the legacy of her husband. For Princess Diana, it was an act of survival, of agency and expression in the stifling horrors of the dynasty she married into. For Maria Callas, the answer is not as clear, and rather than trying to unravel the riddle, Larraín embraces it.

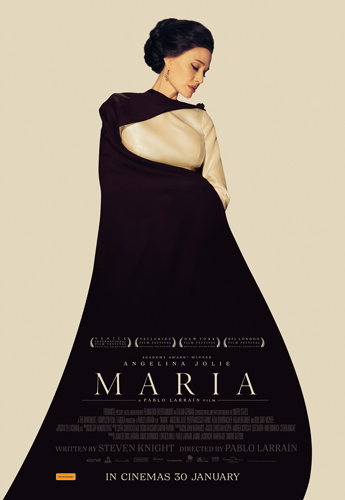

Written by 'Spencer' screenwriter Stephen Knight, 'Maria' follows the same structure as its predecessors by focusing on an enclosed time and place in the life of its subject, using these circumstances as an opportunity to reflect on their lives. We meet Callas (Angelina Jolie, 'Girl, Interrupted') in the last week of her life, living in seclusion at the age of 53 in her ornate apartments in Paris in September 1977, her only companions her manservant Ferruccio Mezzadri (Pierfrancesco Favino, 'Rush') and her housekeeper Bruna Lupoli (Alba Rohrwacher, 'I Am Love'). It has been years since Callas appeared publicly, her voice suffering through excessive medications and ill health. During her days, she visits with vocal coach Jeffrey Tate (Stephen Ashfield, 'Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street') to try and revitalise her voice, but for the most part she finds herself in a reflexive state, talking through her life with a ghostly young man Mandrax (Kodi Smit-McPhee, 'The Power of the Dog') who may be a manifestation of her medication. As her health begins to fail and her grip on reality slips, Callas struggles to come to grips with all she has lost in her rise to fame, with the heartbreaks that led her to become the greatest opera singer of all time and consequently have destroyed her.

Unlike the operatics of 'Jackie' or the theatricality of 'Spencer', Larraín takes a more subdued approach with 'Maria', imbuing it with a subtle magic realism that captures the tragic conundrum of the icon of Callas. She is a woman who both believes herself to be the centre of the universe and completely unworthy of true happiness. These two sides are represented in how she is addressed - early in the film, Mandrax asks if he should refer to her as Maria or La Callas. The latter is the icon while the former is the woman, and the tension in her life is that one does not always leave room for the other, either in her life or in the public perception of her. It's never entirely clear when she is Maria and when she is La Callas, but by this point that uncertainty is a fundamental part of who she is. The only moment of clarity for her is when she sings, the purity of her honesty resulting in a sound that is both intensely human and utterly divine, but much like Terrence McNally's play 'Master Class', 'Maria' finds a Callas incapable of singing at her full power. Her instrument is broken, irreparably. The recordings of the real Callas used in the film, as well as the recreations of some of her great stage performances, populate the film like ghosts. You're always aware of what once was and how that stands in contrast to what she is now. Her isolation, her chilly tempestuousness, her volatile tantrums are an attempt to have some agency over herself, when her greatest gift has been stolen from her.

The consequence of this is her lack of currency in the public sphere, and while she may still garner respect when she enters a room, it is more as another kind of ghost than something more corporeal. Without her voice, she is of less value, and in the moments when her memory slips back to the past, we see how her gift was used to the advantage of more powerful men who wanted to possess it and her. Larraín and Knight pinpoint two key moments - having to perform for Nazi officers during the Second World War as a teenager, and her tempestuous relationship with millionaire Aristotle Onassis (Haluk Bilginer, 'Halloween'), the great love of her life. The latter is more complex, and the film does afford time to explore the intricacies of their relationship. This is another place where the conflict between Maria and Callas is at the forefront, the former's desire for love and security clashing with the latter's need for recognition and respect. Onassis fundamentally does not know which version of her he wants and seeks to strip the agency from both. As a result, when he leaves Callas for Jackie Kennedy, she is left with a broken heart, an unquenchable fury, a building self-hatred and a fractured voice. This is the tragic pressure that builds over the course of 'Maria'; a woman in desperate need of emotional release and expression being rendered incapable of achieving either. There are two key moments where the film does take as fact some of the more persistent (yet unconfirmed) legends about Callas, but it has been careful to link these with the dramatic arc it is exploring, that of a woman at the end of her life trying to take back so much that has been taken from her. Throughout the film, she speaks of finding her "human song", the sound that is so fully and utterly her own, the inevitable tragedy being that she (and we) know she will never find it again.

For those who bristled over the haunted house surrealism of 'Spencer', the similarly surreal moments in 'Maria', though less overt, may have the same effect. Having Smit-McPhee essentially play an antidepressant at first seems a miscalculation, but it's introduced very early in the film and then left to run its course. Without Mandrax, the film would not give Maria anyone to talk openly with and this strange touch does lead to some stirring moments of theatricality throughout the film. Where 'Maria' is at its most powerful though are the moments of intense intimacy, where you feel the sphinx-like armour Callas has constructed for herself start to fall apart. In one of the film's best scenes, she is asked why she doesn't like to listen to recordings of herself. "Because they're perfect," she replies. Perfection leaves no room for expression, for truth, for inspiration. To be perfect - to be Callas - is to be a monolith, an object of permanence, incapable of fault. Maria is a creature full of faults and a world obsessed with Callas has no patience for human faults. For Maria, Callas is her mask, her protection, her prison and her curse.

Pablo Larraín supports Angelina Jolie with the kind of ravishing romanticism we've come to expect from the other films in the trilogy. There's a tremendous intimacy to the way he shoots these films.

As with Natalie Portman and Kristen Stewart, Angelina Jolie delivers a career-defining performance for her entry in Larraín's trilogy. She avoids any histrionics in her depiction of Callas, as well as any obvious attempts at imitation. Where Portman and Stewart grappled magnificently with the iconography of their subjects, Jolie's performance is quieter, subtler, taking its cue from her near-perfect grasp of Callas' careful cadence. Jolie possesses a similar natural grace as Callas, but the real mastery of her performance is the way in which she can manipulate that grace and poise, showing us a woman always on the edge of collapse. The great miracle of her performance - and consequently the film - is her ability to capture the unknowability of Callas while simultaneously inhabiting a truthful, honest inner life for her. It's a magnificent, devastating, deeply moving performance, the kind that haunts you for days afterwards.

Larraín supports Jolie with the kind of ravishing romanticism we've come to expect from the other films in the trilogy. There's a tremendous intimacy to the way he shoots these films, in this case with the legendary cinematographer Ed Lachman ('Carol'). What is most striking about the cinematography in 'Maria' is the way Lachman plays with light - the streets of Paris exist in a perpetual state of magic hour, a golden and ethereal glow, while inner spaces are lit with a subtle yet effective theatricality. The camera is there with Maria in her personal space but never in an invasive way, almost like a companion. Guy Hendrix Dyas, returning to the trilogy as production designer, similarly crafts the spaces with a gentle acknowledgement of the artificiality that surrounded Callas, the need to create a space for herself that reflects her tastes and a safe cocoon reminiscent of the theatres she performed in. Apart from Jolie, the creative with the most acute challenge is Massimo Cantini Parrini as costume designer, tasked with recreating one of the great fashion icons of the last century, but he is careful to make sure that the glamour comes with dramaturgical purpose. At times Callas is more glamorous than you could imagine and other times that glamour feels ill-placed or garish. Callas told her story through what she wore, and Parrini makes sure 'Maria' is no exception.

Larraín once again pulls off some sort of magic trick with his direction here. There's a self-aware opulence to his approach to these films but he ensures that this never comes at the expense of the subject's integrity. His touch is wisely more delicate here, in part to allow the music to do its work but also in acknowledgement of how 'Maria' differs from 'Jackie' and 'Spencer'. Both those films end on an ultimately hopeful note, their subjects finding their agency. 'Maria' moves carefully and compassionately towards Callas' death, determined to afford this tragic figure her necessary grace. The climax of 'Maria' is an overwhelming moment, the longed-for marriage of the human and the divine, where the deliberate choices of the filmmaking and the gentle build of Jolie's performance reach their zenith. Where tragedy is the force to overcome in 'Jackie' and the spectre that sits around the edges of 'Spencer', it is at the core of 'Maria', and you're left in an exquisite state of bereavement. Even with its weird quirks and ever-so-slight missteps, 'Maria' is a powerful, devastating film, a worthy portrait of a woman who, ultimately, was unknowable even to herself.

So now that Pablo Larraín's trilogy is complete, what do we make of it? What are the threads that hold these three films together, artistically and thematically? All three explore the lives of women whose positions in society place them even above celebrity or fame. They were all expected to be impeachable, inhuman, icons of their time, impossible to emulate but fascinating to observe. The pedestals they were placed upon were so high as to be unreachable, and consequently extremely lonely. The genius of Larraín's approach, where his magic realism or surrealism serves as an inspired choice, is to balance our hunger for the iconic with the need to see these women as human beings. The overtly aesthetic choices preserve their theatricality, but as all great melodrama should, reveals a deeper truth that realism cannot always address with the same kind of potency. We understand Jackie's confusion and grief as she cycles through her wardrobe, dress after dress, with a recording of 'Camelot' playing in the background. We understand Diana's suffocation and self-loathing as she tears her pearl necklace apart and eats the pieces. We understand Maria's need to be loved and adored as a chorus of men sing to her in the streets. Larraín may not offer us a concise summary of the life and times of these women with these films but, I would argue, offers something far more profound - he brings us closer to understanding the souls behind the icons.

Maria Callas was criticised in her lifetime for prioritising truth in her performances over perfect pitch and tone. Her sound could be harsh, confronting, strange, even ugly, if the truth of the aria required it. In a way, this makes her a perfect closing act for Larraín's trilogy. These films are stories of women trapped in gilded cages, clawing and biting and fighting to find their way out. The films are operatic because the cages are gilded; the performances are enormous because their subjects are beyond human; the narratives enter the surreal because these are our modern myths and legends - the queen left to carry the legacy of a king, the princess trapped in the crumbling castle, the goddess who lost her immortal powers.

The triptych of 'Jackie', 'Spencer' and 'Maria' are, in my opinion, that rarest of achievements in cinema - a perfect trilogy.

To celebrate the release of 'Maria' in cinemas, we're giving you the chance to win a double pass.

To celebrate the release of 'Maria' in cinemas, we're giving you the chance to win a double pass.

To win one of five double passes thanks to Kismet Movies, just make sure you follow both steps:

| 2 |

/toppic/maria.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/rating/M.png)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/the-accountant-2.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/nt-live-dr-strangelove.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/sinners.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/drop.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/warfare.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/death-of-a-unicorn-2.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/a-goofy-movie.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/a-minecraft-movie.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/dog-man.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/a-working-man.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/hotfuzz.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/theshepherd.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/endofthecentury.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/gallipoli.jpg)

/filters:quality(75)/toppic/thetroublewithbeingborn.jpg)